- Published on

Git Internals

Table of Contents

- Plumbing vs. Porcelain

- .git Folder

- Addressing Compatibility Issues

- Anatomy of .git Folder

- Comparison to File Systems

- Git Objects

- Creating Them

- Git Checksums:

- Object Types

- Object Anatomy

Plumbing vs. Porcelain

- the porcelain is the high-level commands for the end users

- the plumbing part of a program is the low-level part, where the actual work is done. It is not easy to use and not meant to be easy

Git actually violates a common software engineering rule, which is "Just show the porcelain to the outside world. Don't expose your plumbing.

Instead, Git wants to have two levels. Even at the low-level, it wants to expose its basic model for how Git works if the user is willing to understand how it works.

.git Folder

The entire state of the repository is encoded in the special .git directory.

Addressing Compatibility Issues

- When a new version of Git comes out, it needs to be able to work with old repositories (to maintain backwards compatibility)

- The converse is not always true; repositories created by recent versions of Git may not necessarily work with older versions of Git

- therefore there are some files in the

.gitfolder that are archaic.

- therefore there are some files in the

Anatomy of .git Folder

branches- obsolescent - will appear when there are branches within the thing (for backwards compatibility mostly)config- repository-specific configuration (very standard)- tends to act as the barrier to git providing important information about the repository

description- used for GitWeb, an attempt to put Git on the web (somewhat obsolete)HEAD- where the current (default) branch ishooks/*- executable scripts that Git will invoke at certain "pressure points" (important triggers, like making a commit). By default, there are no working hooks; default ones all end with.sample, which illustrate what you might want to put in such hooks.- changing the config files will change the hooks most of the time

- main purpose of Git hooks is to allow developers to automate and customize their Git workflow based on their specific needs and preferences

index- a list of planned changes for the next commit in a binary data structure- the on file representation of what the future looks like

info/exclude- addition to.gitignore.- .gitignore is a working file while this is private to a specific repository

logs- keeps track of where the branches have been (histories of branch tip locations).objects- where the actual "repository" is, where the object database is stored.- object database contains pointers to the objects, and the objects point to each other

- subdirectories are 2 hexadecimal digits and then 38 hexadecimal digits

- you need to compute the checksum for the object

- Using only two digits for the subdirectory name strikes a balance between avoiding having too many subdirectories while still ensuring a good distribution of files across them

refs- where the branch tips and tags are (where all the "pointers" in the repository are).packed-refs- optimized version ofrefsthat are less often updated- we are building one data structure atop of another

Emacs Hooks ASIDE: Because

git clonedoes NOT copy hooks, fresh local copies of a repository always have no functioning hooks. Emacs maintainers went around this by preparing a script in the Emacs source code calledautogen.sh. This script creates a bunch of Git hooks that tailor the repository to be the way the Emacs developers want it to be tailored. This is a nice "gatekeeper" approach that ensures your development is relatively clean.

Comparison to File Systems

| Similarities | Differences |

|---|---|

| hierarchial directory structure & directed acyclic structure (git) | git is built atop regular file system |

| similar issue is stores metadata of objects and files | git's naming convention is dependent on the contents of the object, while inode is independent from the mutable files |

| uses a standard naming convention | Files in the filesystem can be mutable |

| provides a set of commands and APIs for interaction | -- |

| another issue is use low-level atomic instructions for durability including crashes/network | -- |

| both directed acyclic graphs. In the filesystem, it's guaranteed by the OS that you cannot have cycles. For Git objects, you cannot create a cycle because you can only add to history, not change it. | -- |

- A local Git repository and the index are made up of objects and some other auxiliary files

- Files in the filesystem can be mutable. inode numbers thus exist independently of the contents of their files

- checksums uniquely identify objects by their content. Therefore, you cannot change objects' contents.

Git Objects

Creating Them

- blob: represents any bytes sequence, like regular files in a file system

- We convert the blobs to the git hash checksum using the SHA hashing algorithm from the blog

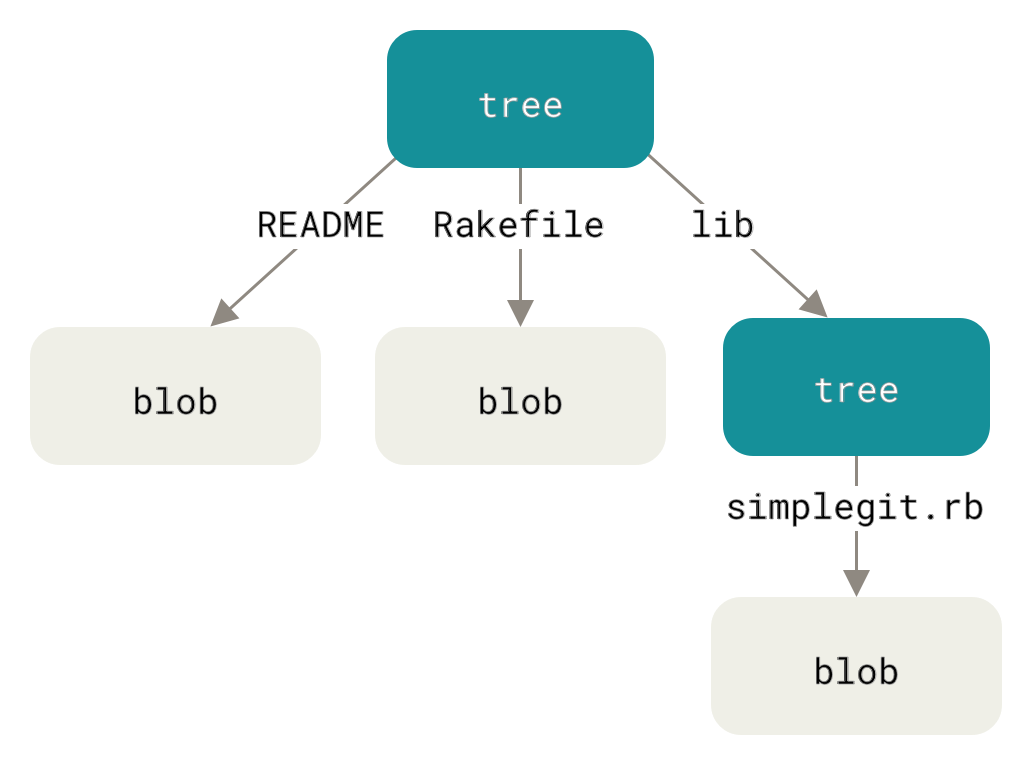

- tree: represents a node in a tree of objects; maps names to SHA-1 checksums of blobs or other tree

Git Checksums:

- Git Checksum a cryptographic checksum has three properties:

- the probability of any hash is 1/2^n where n is the number of bits (160 for SHA-1)

- finding a byte string to match a given hash is O(2^n) there is no practical way to reverse the hash to the object,

- the commit id gives you no information since it is a one way hash Generate a checksum from string content:

- finding a collision is order of order 2^(n/2)

- cryptographic hashes were created to see if there was tampering of messages when they are being sent, but these are obsolete because SHA-1 has been cracked

- The security of git depends on the security of the underlying file system, and its not common for people to want to find the files based off of the commit id

people who want to corrupt the git repo using collisions (2 similar git commits), will not be able to due to system restrictions. This is why SHA-1 is still in use.

$ echo 'Arma virumque cano.' | git hash-object --stdin

24b390b0e3489b71977f5c7242a4679287349242

You can also supply a file name as a positional argument instead of using --stdin.

Computing the checksum and writing it to the repository:

$ echo 'Arma virumque cano.' | git hash-object --stdin -w

24b390b0e3489b71977f5c7242a4679287349242

Notice that the file has 444 permissions. No one is allowed to write to this file.

But there's always a troublemaker!

chmod u+w .git/objects/24/b390b0e3489b71977f5c7242a4679287349242

You're technically allowed to do this, but in doing so, you're violating an invariant that Git trusts in order to properly function, so live your with your consequences I guess.

Object Types

- blob: represents any bytes sequence, like regular files in a file system

- similar to the file within the file system

- tree: represents a node in a tree of objects; maps names to SHA-1 checksums of blobs or other tree

- similar to the directory within the regular filesytem

You can see the organization in action with something like:

$ git cat-file -p 'main^{tree}'

100644 blob dfe0770424b2a19faf507a501ebfc23be8f54e7b .gitattributes

100644 blob 6560eb3e95e2524af2e9ebd58f4b83b9192fa72d .gitignore

100644 blob 19750c76aa49ca16ca2f595e67b0add5b7e91866 README.md

040000 tree 165384a697bd26dc2058347f8021d8d7835a4344 assign1

040000 tree 0cea65060dcfd514a50c7b37f51cef0fee7866ba assign2

040000 tree 0c26a808301312e196d2d0e2ad23d589f4ff363a assign3

040000 tree e60417a5d19ce58e4ff7d642d1da31bbe2dcfe3c assign4

160000 commit 3e3ecd9922a1e7924585afc71865dfacce2715ae assign5

040000 tree 650431ccc6c447aad3dc1e7d0508b344495f9c4f notes

040000 tree f892a3a8636d6b6a610670a3e909cc3d3d8f830f pdfnotes

Each commit points to a tree. The tree is like a directory in a file system. Above, main^{tree} refers to the tree object referenced by the commit object referenced by the branch named main. The tree tells git where to look for the subobjects within the tree. Each of the blobs will tell us what is in the working file

100644 blob 6560eb3e95e2524af2e9ebd58f4b83b9192fa72d .gitignore

(mode)(type) (SHA-1 checksum) (name)

- 1st column: octal digits, the last three of which represent the Linux permissions of the file in question (so

644meansrw-r--r--). - 2nd column: the type, blob, another tree, etc.

- 3rd column: the SHA-1 checksum of the referred object. After all, a tree just represents a pointer to a bunch of other objects.

- 4th column: the name of the file.

Object Anatomy

Every commit object points to two things. First is the identification of the tree the commit represents. The second is the parent commit object(s) since the gits are related to each other.

$ git cat-file -p main

tree e44cfad85dda09495f8f39ecfb4db8bc1a4db876

parent 7ca43260f9af838721829aff02a9c4b2aac9ef3f

author Apurva Shah <shahh.apurva@gmail.com> 1678175808 -0800

committer Apurva Shah <shahh.apurva@gmail.com> 1678175808 -0800

Git Notes

We see that every commit object contains information about its parent, author and committer.

You can think of git log (a porcelain command) as pretty-printing what cat-file -p REF (a plumbing command) tells us.

Three levels going on with every commit object:

(commit object)...

|

| +---------> (other objects)

v |

(commit object) --> (tree object) --> (other objects)

| |

| +---------> (other objects)

v

(commit object)...

Every commit points to a different tree, but the tree can share the objects they reference. When you make a commit for small changes, you don't have to rebuild a bunch of objects. Unchanged objects are reused.

However, because changing a file would update the tree containing it, changing a deeply nested file would require new tree objects all the way up to the project root for the new commit.

If a file is extremely large, Git can store a diff instead of a full copy and just remember how to restore the full content when the blob is needed.

- Authors

- Name

- Apurva Shah

- Website

- apurvashah.org